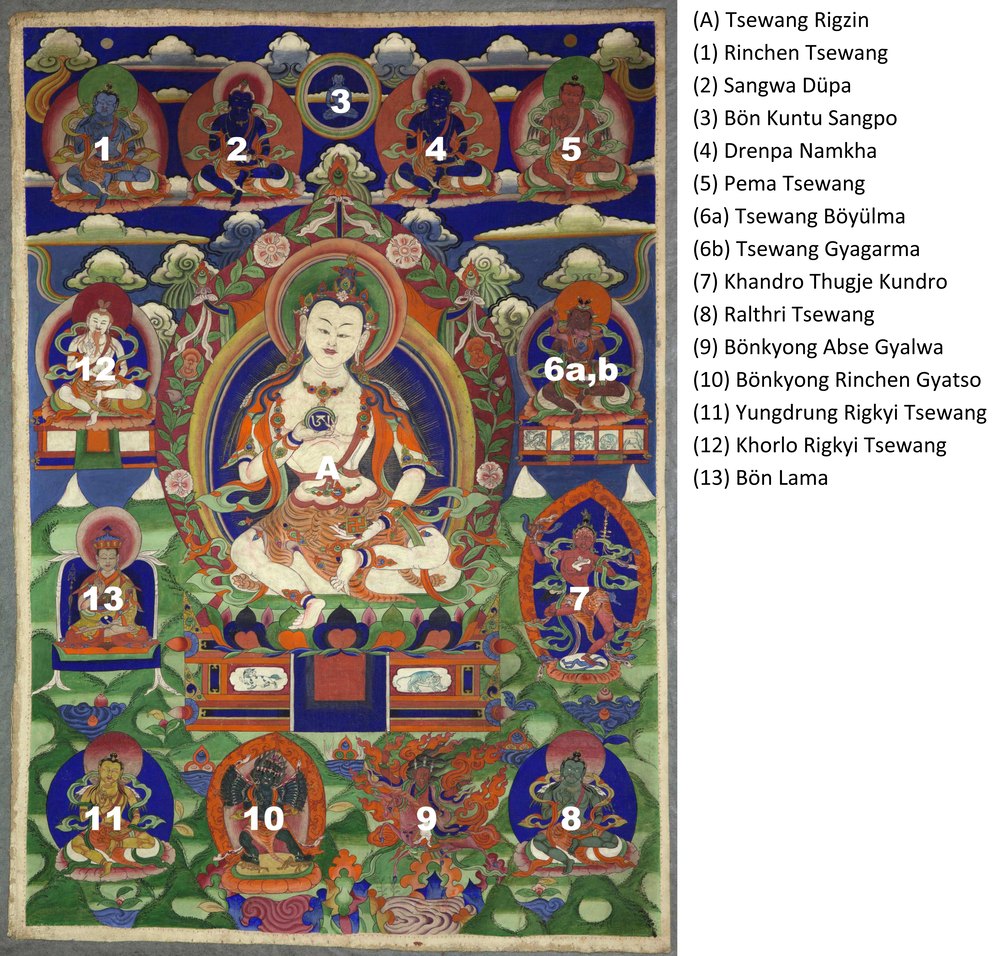

_mnao.jpg)

Bon po deity Tsewang Rigzin (Tshe dbang rig ’dzin)

19th century CE

Tradition: Bon

Tibet: Amdo (?), East Tibet

Tucci received this thangka in Lippa, Kinnaur, Himachal Pradesh, India in 1931

Pigments with a water miscible binder on cloth,

60 x 43 cm (with cloth frame? 126 x 90 cm)

MNAO, inv. 922/755

Published in Tucci (1949b: no. 120, pl. 155, p.553–54); Lo Bue (1983: no. 25, pp. 50–51)

Tucci was given this thangka in Lippa, Kinnaur in 1931 by Namkha Jigme Dorje (Nam mkha’ ’jigs med rdo rje), who was first educated in the Bon tradition but then became a Nyingma Buddhist Master of the Dzogchen (rdzogs chen) tradition. He obtained the thangka in Western Tibet. Tucci says he was “one of the most cultivated men I met in Tibet”. (1949b: p. 554). In 1935 Tucci met in Gartok, Tibet a very famous Dzogchen Master from Kham who was a companion of Namkha Jigme Dorje, at that time still said to be living in Kinnaur (Tucci and Ghersi 1935, reprint 1996: pp. 148–49). This small story demonstrates how widely networked the Tibetansname | nametibtrans | namtib were despite the extraordinarily difficult terrain and how successfully Tucci fit himself into this network of distinguished Tibetans. This thangka is dedicated to the Bon Long Life deity Tsewang Rigzin (Tshe dbang rig ’dzin), who is considered to be a siddha in the Bon po tradition (A). The distribution of space is constructed around the Pentad as in Vajrayāna Buddhism.FN1 Tucci (1949b: p. 554) draws attention to the relationship between the Buddhist Amitāyus (e.g. cat. 46) and the Bon deity Tsewang Rigzin. Dating to the late 19th century, the Bon painting derives some of its compositional and iconographic principles from the Nying ma Nyingma Buddhist tradition. The main deity is frontally represented on the central axis and larger than all other figures in the composition. At the very highest plane and at the centre on the axis is the supreme deity of this particular pantheon, in this case Bon Ku Kuntu Sangpo (Bon sku Kun tu bzang po) (3), and at the lowest level at the centre are the protector deities (skyong). In the Yoga Tantra system of Buddhism, the Jina Vairocana, who is associated with the colour white, is placed in the centre and the other four Jina Buddhas of the Pentad surround him. The following schema is the one followed by Tucci (1949b: p. 554) who received the explanation from the lama who gave him the painting. The colours of the Bon Pentad are the same as in Buddhism, but their symbolic function is different. The names of the families in the Bon Pentad at least in three cases do not exist in Buddhism: Sword, green; Swastika, yellow; Wheel, white. Two families exist in Buddhism, but the colours associated with them are different than here, Gem family is blue; and Lotus family is red. The name of at least one deity in each “family” is indicated in their name, and of course, their colours appear in the painting according to the textual description. At the centre we have two forms of Tsewang Rigdzin (A). The main figure holds an “A” in his right hand and in his left hand he holds a left turning swastika. To his proper left is the yab yum form Tsewang Böyülma (Tse dbang bod yul ma) who is red (6a); his consort Tsewang Gyagarma (Tse dbang rgya gar ma) is rose/red (6b). The five animals located on the throne of Tsewang Böyülma are dragon, bird, lion, elephant, and horse.FN2 Red is also the colour of Amitāyus, one of the most important Long Life deities in Vajrayāna, who belongs to the family of Amitābha.